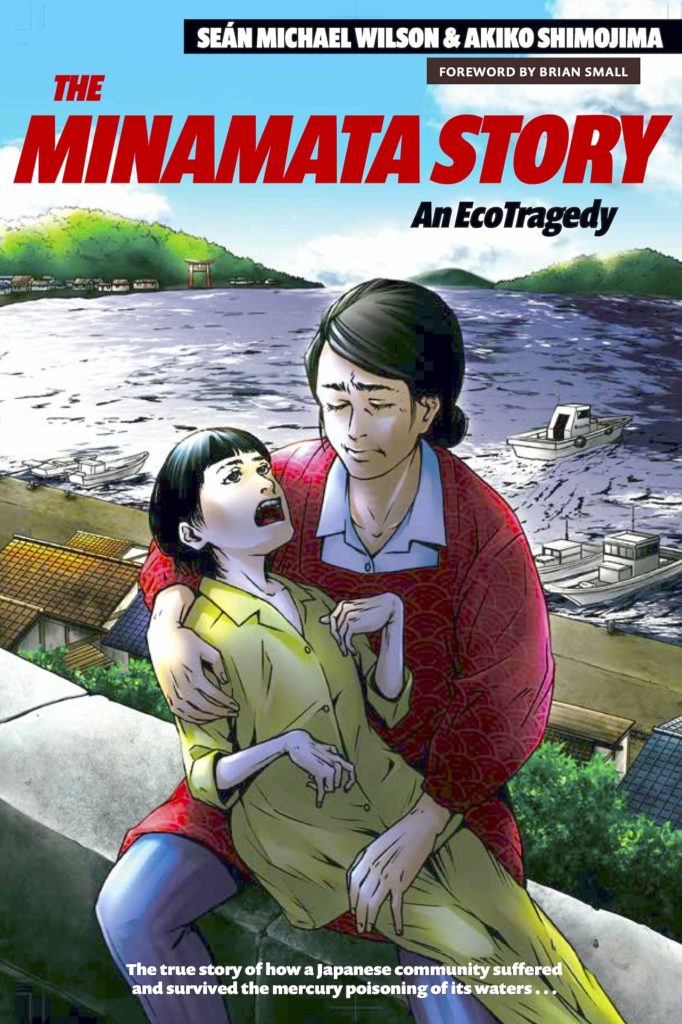

“In lots of places around the world young people are protesting against injustice and environmental damage. Whatever their theory or language or culture is, the basic aim is the same: they are trying to make things better. I think we should be doing the same in Japan. And from now on, I will” — Tomi, The Minamata Story: An Ecotragedy, p. 101.

| Creator(s) | Seán Michael Wilson (author), Akiko Shimojima (illustrator) |

| Publisher | Stone Bridge Press |

| Publication Date | 2021 |

| Genre | Fiction, Manga |

| Environmental Themes and Issues | Animals in Danger, Corporations, Environmental Activism, Environmental Justice, Habitat Destruction, Ocean Conservation, Pollution, Recycling |

| Protagonist’s Identity | Tomi: A half Asian, half white British college Student |

| Protagonist’s Level of Environmental Agency | Level 4: Considerable Environmental Agency without Activism |

| Target Audience | Young Adult |

| Settings | Minamata, Japan |

Environmental Themes

Seán Michael Wilson and Akiko Shimojima’s young adult manga The Minamata Story: An EcoTragedy educates readers about Minamata disease, a debilitating and sometimes fatal neurological condition in humans and animals caused by the consumption of fish contaminated by methylmercury. Thousands of residents of Minamata, Japan developed the illness after the Chisso chemical factory illegally released toxic chemicals into the Yatsushiro Sea in the 1950s and 60s. The Minamata Story investigates the enduring effects of this pollution through the perspective of Tomi, a contemporary half-British, half-Japanese college student. Tomi visits Minamata with his grandmother, Kimura, to learn about the disease after he selects the illness as the subject of his class research project.

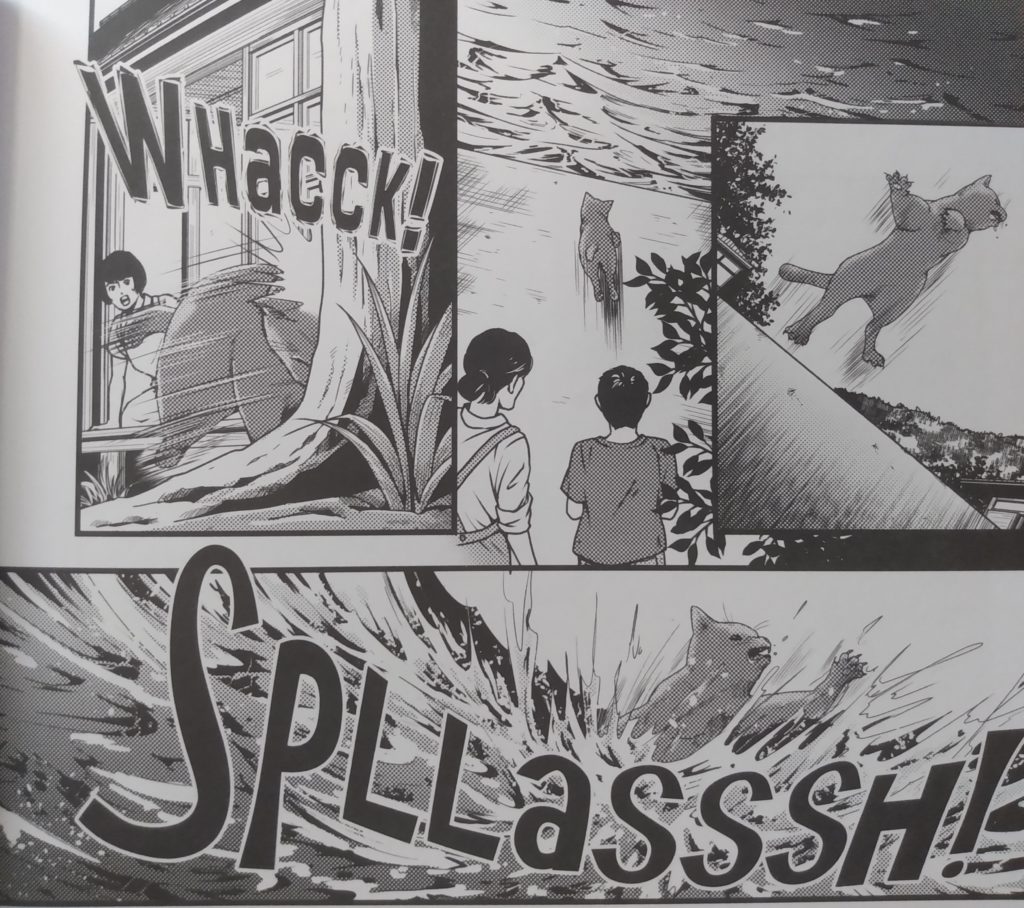

Set in the 1950s, the manga’s opening scene highlights the environmental devastation caused by the pollution through a series of mostly-wordless illustrations. First, two panels depict a silhouetted person traveling in a small boat in the Yatsushiro Sea, backdrop by a lush landscape and the setting sun. On the following page, however, the titular “ecotragedy” interrupts this idyllic nature scene. A pipe spews dark toxic waste into the ocean, and the pollution invisibly travels through the ecosystem, moving from shrimp to a series of ever-larger fish that are harvested by fishermen. Domestic cats consume the caught fish and soon develop horrifying symptoms of Minamata disease, also known as “dancing cat syndrome” due to the convulsions it causes in animals. The scene concludes with a cat stumbling around in a daze before plunging into the ocean and drowning as its owners watch in horror. This troubling opening educates readers about the origins of Minamata disease and makes it clear that the ecotragedy did not only harm human victims.

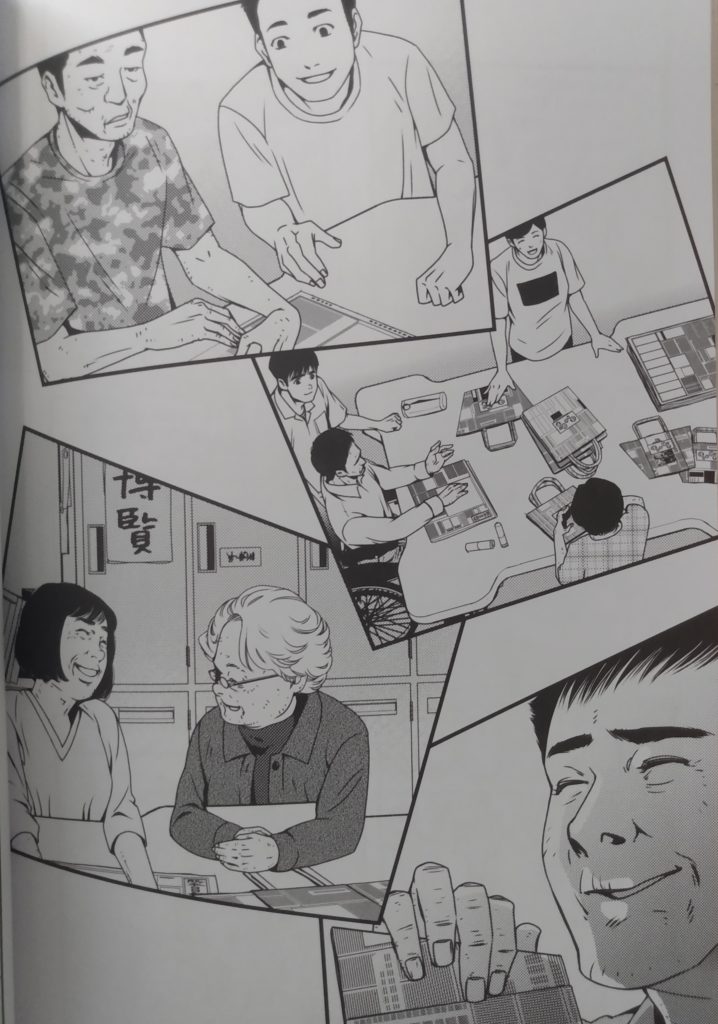

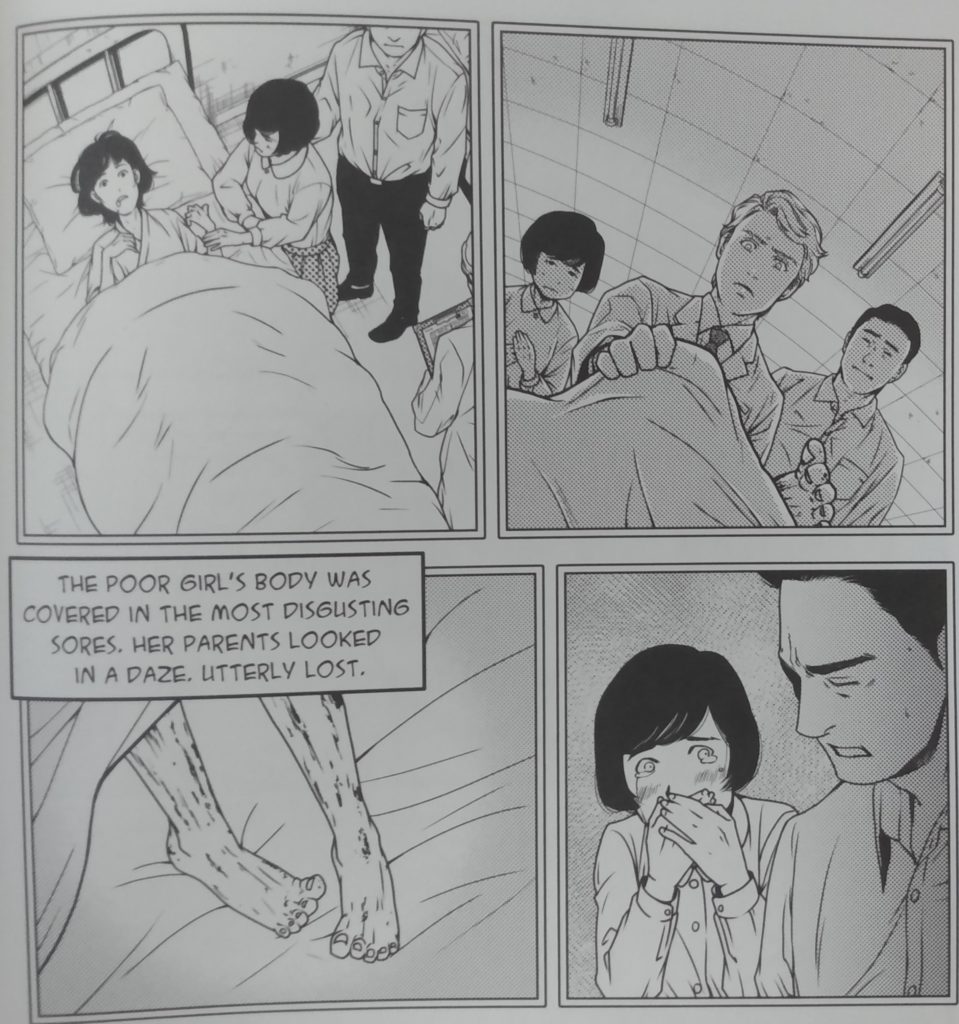

After the disturbing opening scene, the manga leaps forward to the present day as Tomi receives the topic of his assignment and travels to Minamata with his grandmother, who lived in the town during the crisis. They visit Hotto Hausu, a community center and workplace for people who suffer from Minamata disease. The survivors produce and sell “eco-bags” and bookmarks made from recycled materials and give talks to schoolchildren to educate them about the ecotragedy. As Tomi meets with the survivors and other firsthand witnesses to the crisis, he learns that the pollution was a form of environmental injustice that affected Minamata’s most vulnerable residents. For instance, his grandmother explains that the town’s fishermen lost their source of income after the local fish retailers union refused to sell fish caught locally. She recalls a furious fisherman telling a retailer, “You selfish lot, how can we feed our families if you don’t sell our fish!” The retailer responds, “We can’t sell poison fish, idiot!” and the street erupts into a violent brawl between the two sides (Wilson and Shimojima 21). Compounding the issue, the Chisso corporation initially refused to admit that their pollution was contributing to the disease. When the company was eventually found legally liable, it only financially compensated a portion of the people impacted by the disease. As a doctor tells Tomi, only 2,265 out of the more than 17,000 people who applied for certification as Minamata disease sufferers were approved for compensation. By emphasizing the economic, medical, and social consequences of the pollution, the manga offers a scathing critique of Japan’s failure to adequately address the environmental crisis.

After learning about Minamata disease, Tomi decides to participate in environmental activism. During a presentation to his class about the disease, he asks the other students, “What are you doing to help make things better? In lots of places around the world young people are protesting against injustice and environmental damage. Whatever their theory or language or culture is, the basic aim is the same: they are trying to make things better. I think we should be doing the same in Japan. And from now on, I will” (Wilson and Shimojima 100-101). This speech serves as a call to action for young adult readers, inviting them to consider how they can engage in their own forms of environmental and social activism. However, the manga does not depict Tomi engaging in activism–except for educating the other students about Minamata disease in his presentation–and it also doesn’t directly suggest ways that readers can engage in advocacy. Overall, though, the manga effectively educates readers about the Minamata environmental crisis and reveals the intersections between environmental injustice, disability, and socioeconomic inequality.

Additional Resources

On July 26, 2021, author Seán Michael Wilson gave an author talk with the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California. View the full recording here: https://www.jcccnc.org/author-talk-the-minamata-story-an-ecotragedy-with-manga-author-sean-michael-wilson/.