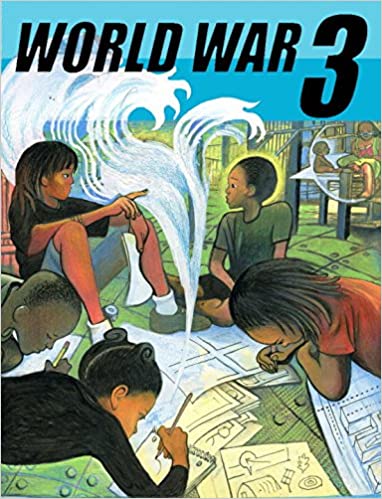

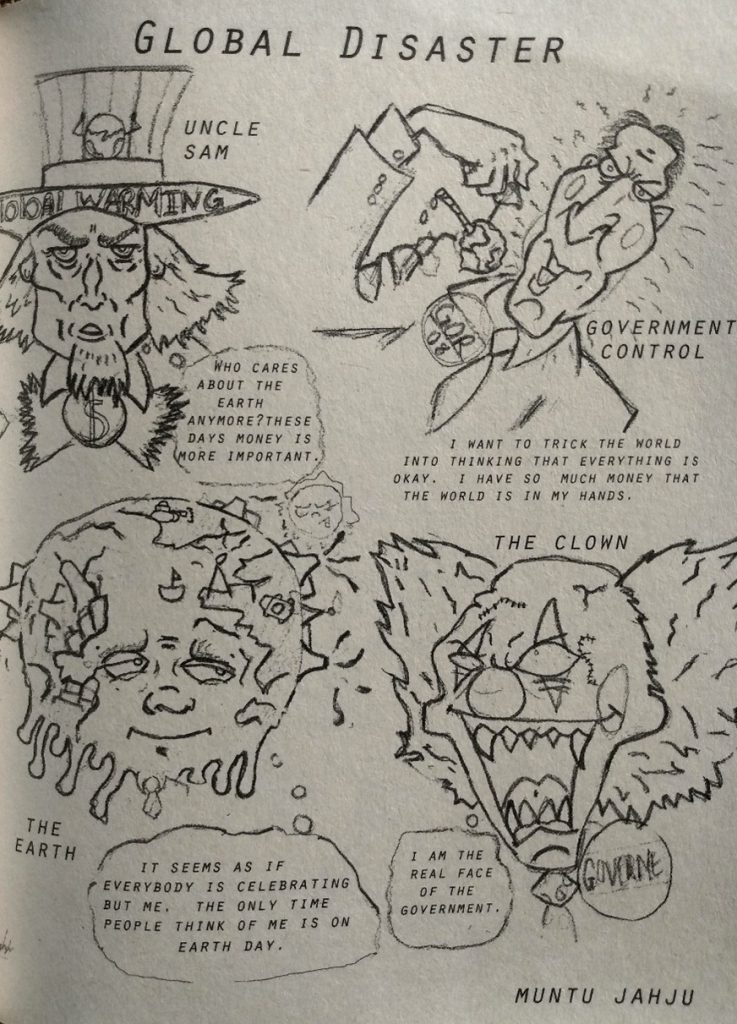

“Who cares about the Earth anymore? These days money is more important” — Uncle Sam in “Global Disaster,” World War 3 Illustrated #46, p. 53.

| Creator(s) | Hilary Allison (editor), Paula Hewitt Amram (editor), Sandy Jimenez (editor), and various other contributors |

| Publisher | Top Shelf Productions |

| Publication Date | 2015 |

| Genre | Anthology, Zine, Fiction |

| Environmental Themes and Issues | Climate Change, Habitat Destruction, Fuel Extraction or Shortages, Overfishing, Pollution, Marine Pollution, Nuclear Disaster, Species Extinction, Extreme Weather |

| Protagonist’s Identity | The different zines include diverse casts with both male and female characters. Some of the zines also feature characters of color. |

| Protagonist’s Level of Environmental Agency | Level 4: Considerable Environmental Agency without Activism |

| Target Audience | WW3I primarily addresses an adult audience, but this issue includes |

| Settings | Miscellaneous settings |

Environmental Themes

First published in 1979, each installment of World War 3 Illustrated (WW3I) centers on a different political issue and features zines and other imagetexts produced by a large and constantly changing cast of activist creators. For the first time in the zine’s history, WW3I #46 grants a voice to an often overlooked marginalized group that has “the most at stake” when it comes to environmental issues: children and teenagers (Allison, Editors’ Note). The issue prominently features zines produced by young people—often in collaboration with parents, teachers, and other youth—alongside the work of seasoned adult zinesters, such as Peter Kuper and Kevin Pyle. These multi-generational contributions explore “two overlapping themes: our planet’s growing climate crisis and how young people are confronting the ‘climates’ they have inherited—social, political, cultural, and especially, environmental” (Allison, Editors’ Note).

For instance, J. V. L. Wildcat Academy student Muntu Jahju’s one-page zine offers a scathing critique of capitalism, oil extraction, and even democracy itself as inherently destructive and anti-environmentalist. The zine depicts four hand-drawn caricatures: Uncle Sam, whose signature striped hat has been transformed into a cage imprisoning a tiny planet Earth and bearing the words “Global Warming” on the brim; a businessman labeled “Government Control” who wears a suit and dangles a small Earth impaled with a leaking oil pipe; an anthropomorphic, sweating planet Earth covered with manmade smokestacks emitting pollutants; and a leering, scarred clown labeled “Governe [sic]” (Figure 1) (Allison 53). Beneath each of these drawings, a typeset caption or thought bubble expresses the characters’ views on the impending “Global Disaster” heralded by the zine’s title. For instance, Uncle Sam thinks, “Who cares about the Earth anymore? These days money is more important,” while the forlorn Earth reflects, “The only time people think of me is on Earth Day” (Allison 53). Together, the zine’s images and text portray American society as corrupt and greedy, with each of its familiar yet distorted archetypes—the Earth-imprisoning Uncle Sam, the businessman, and the clown, who declares himself the “real face of the government”—abusing the environment for profit (Allison 53).

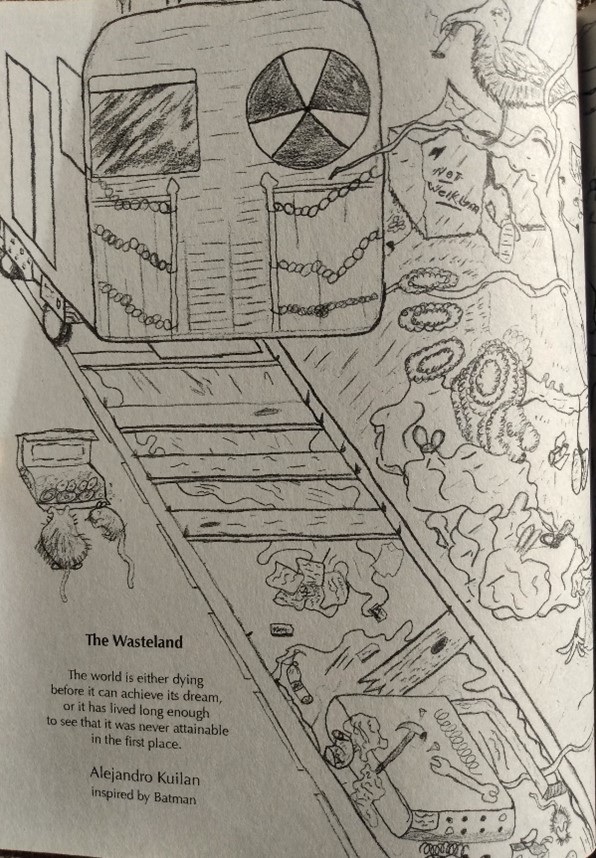

Similarly, Alejandro Kuilan’s “The Wasteland,” another zine produced by a J. V. L. Wildcat Academy student, borrows familiar images from popular culture to confront readers with their own complicity in climate change and provide a dire warning about the potential consequences of environmental destruction. As the title suggests, the two-page zine portrays a ravaged landscape filled with images of ruin and destruction: a railway covered with food wrappers, a barren tree studded with lightbulbs and electrical sockets, sickly birds, a pipe belching oil onto the ground, factories spewing smoke into the sky, and a train with a radioactive symbol. Alongside this jumble of dystopian imagery, a one-sentence poem with accompanying paratext appears at the bottom righthand side of the spread: “The world is either dying before it can achieve its dream, or it has lived long enough to see that it was never attainable in the first place” (Allison 54). The poem alludes to a well-known line of dialogue spoken by Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight Batman film: “You either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.” Kuilan appropriates and remixes icons of mass culture—the Batman quote, the radioactivity symbol, packages of junk food, and so on—to confront readers with the villainy of everyday human actions and industrialization, rather than the supervillains figured in American popular culture.

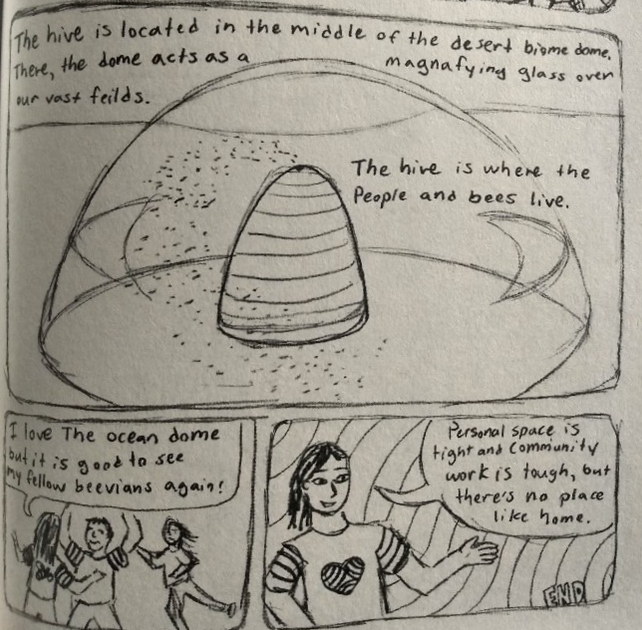

Other youth contributors provide more optimistic portrayals of the future. “The Future” sub-collection features eight zines produced by child participants during a workshop hosted by WW3I contributor Rebecca Migdal. “Untitled,” a two-page zine created by eleven-year-old Isabella Ulfelder, centers on a teenage girl who visits the surface of the Earth before returning to her home under the ocean, a living situation enabled by a bubble-like machine that she wears over her head. Similarly, in sixteen-year-old Rebecca Goldin’s “Untitled,” protagonist Aspen is an “extreme farmer” who lives in a community-centered, hive-like biome dome inhabited by both people (referred to as “beevians”) and bees. “The Thingabobs,” a zine produced by Jasmine Posner and perhaps inspired by Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax (1971), depicts the titular creatures as cartoonish, anthropomorphic blobs who destroy their own planet by mining and building factories. In “Super Cat Vs. Leon” by Nandi Loizzo, a talking superhero cat tries to save the world from global warming but discovers to his dismay that Leon doesn’t believe in climate change.

The zine anthology also includes various environmentally related contributions from adult cartoonists. For instance, Peter Kuper’s “Migration,” an excerpt from his graphic novel Ruins, depicts the migration of a monarch butterfly and includes facts about the species. Likewise, Jordan Worley’s “Bounty of the Sea” takes place in a future when most fish, except for jellyfish, have disappeared as a result of overfishing, climate change, and pollution. Over dinner, a family discusses the destruction of the ocean and the Earth due to harmful human actions. In a satirical epilogue, lawyers break into the house and issue the family a cease and desist, ordering the family to “stop using the terms: climate change and global immediately! How can the planet be warming when we still have winter? Besides, our clients hold a copyright on those two terms!” (Allison 21). Together, the zine anthology’s contributions address a broad range of environmental issues, ranging from climate change to fossil fuel extraction to overfishing.

Paratexts

Issue #46 includes various paratexts, many of which seek to explain or promote the contributions of the youth zinesters. For instance, Lisa Wilde, an English teacher at J. V. L. Wildcat Academy, wrote a one-page introduction that precedes her students’ contributions. She briefly describes each of the zines and the youth creators’ role in producing them, as well as emphasizes the teenagers’ marginalized status as at-risk students. Additionally, Rebecca Migdal’s two-page introduction prefaces “The Future” sub-collection. Migdal includes an anecdote about a young female participant who wept and had to be removed from the workshop after hearing Migdal talk about climate change. “I bet she’s not the only child losing sleep about climate change,” Migdal reflects, adding, “Considering their relatively powerless position, looking to an unavoidable future when the planet is irrevocably transformed has to be terrifying. Not surprisingly, the comics created during the workshop use displacement to make the subject matter bearable” (Allison 111). Migdal casts all of the child artists as fearful and “relatively powerless,” despite the fact that zines like Goldin’s untitled extreme farmer narrative provide optimistic portrayals of the future. Additionally, Migdal also influences the reader’s interpretation of the youth zines by providing a one- or two-sentence summary of each text, suggesting that children’s art requires adult interpretation to render them meaningful or understandable.